Tokelau’s past may help determine Olohega’s future

This guest post is by journalist, producer and communications professional Samson Samasoni. Whilst he is widely published and respected, he is most well known to us as the director of our launch video.

The theme for the 2022 Tokelau Language Week, hosted in Aotearoa, New Zealand by the Ministry of Pacific Peoples is:

Halahala ki vavau, kae ke mau ki pale o Tokelau

This means:

To plan for the future is to understand the past.

When Tokelau’s parliament the General Fono met in May, this curious statement appeared in one of the meeting papers - “Develop a strategy for Olohega”.

The reference was in relation to whether Tokelau should again start discussions about its potential future and pathway towards self-determination. The Fono agreed that it should, especially as it heads into commemorating 100 years under New Zealand administration in 2025/26.

Tokelau is a non-self-governing territory that has been administered by New Zealand since 1926. It has three potential options for its self-determination: full independence (like Samoa); self-governing in free association with New Zealand (like Niue and the Cook Islands); or full integration with New Zealand (like the Chatham Islands).

An earlier attempt in 2006 and 2007 for Tokelau to decide its future was unsuccessful, as not enough Tokelauans supported the change to self-government in the referendum conducted.

But 15 years on, in agreeing to restart self-determination discussions, Tokelau has also agreed that a strategy for OIohega should be developed. So why is this curious?

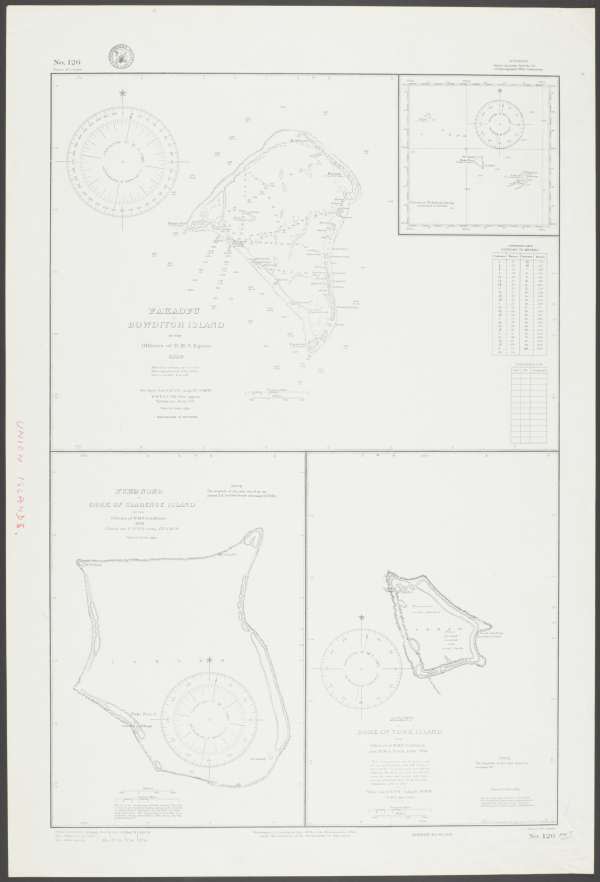

Tokelau is made up of three tiny atolls in the Pacific Ocean – Atafu, Fakaofo and Nokunonu –about 500 kilometers directly north of Samoa. It has a total land area of about 12 sq kms, inhabited by only 1,500 people.

Source: United States. Hydrographic Office. (1941). Union or Tokelau Group Retrieved October 27, 2022, from National Library of Australia.

But Olohega is the fourth atoll.

Tokelauans have and still consider Olohega traditionally and culturally part of Tokelau. But it is the subject of an ongoing territorial dispute with the United States, which has administered the island as part of American Sāmoa since 1925.

Given the David and Goliath proportions of the dispute, the notion of coming up with a strategy suddenly becomes intriguing.

Originally Olohega was known by Europeans as Gente Hermosa or Quiros Island, after Portuguese explorer Pedro Fernandez de Quiros, who believed he discovered it in 1606. However, it’s now widely accepted that what he saw was actually Rakahanga, which is part of the Cook Islands.

This map referring to the atoll as 'Gente Hermosa' is held by the Boston Public Library, and is part of the nautical maps collection of the US Exploring Expedition of 1838-1842.

![United States. Hydrographic Office, & United States Exploring Expedition (1838-1842). (1887). Gente Hermosa or Swains Island ; Jarvis' Island ; Birnies Island, Phœnix Group ; Enderbury' Island, Phœnix Group ; Hull's Island, Phœnix Group ; New-York or Washington Island [Map]. Retrieved from https://ark.digitalcommonwealth.org/ark:/50959/5d86rh44m](https://images.ctfassets.net/iujh0vzmw6xm/wiChqXR2XHrCCEFkqvu1d/5223139b1d7deb09603371ef688b8cad/commonwealth_5d86rh44m_image_access_800.jpg)

Source: United States. Hydrographic Office, and United States Exploring Expedition (1838-1842). Gente Hermosa or Swains Island ; Jarvis' Island ; Birnies Island, Phœnix Group ; Enderbury' Island, Phœnix Group ; Hull's Island, Phœnix Group ; New-York or Washington Island. Washington, D.C.: Hydrographic Office, 1887. Web. 28 Oct 2022.

Today Olohega is better known as Swains Island, after Captain William Swain, the master of the whaling vessel George Chaplin, when he came across the island in either 1850 or 1851. However, there’s another view that this too may have been an erroneous, potentially "forged discovery".

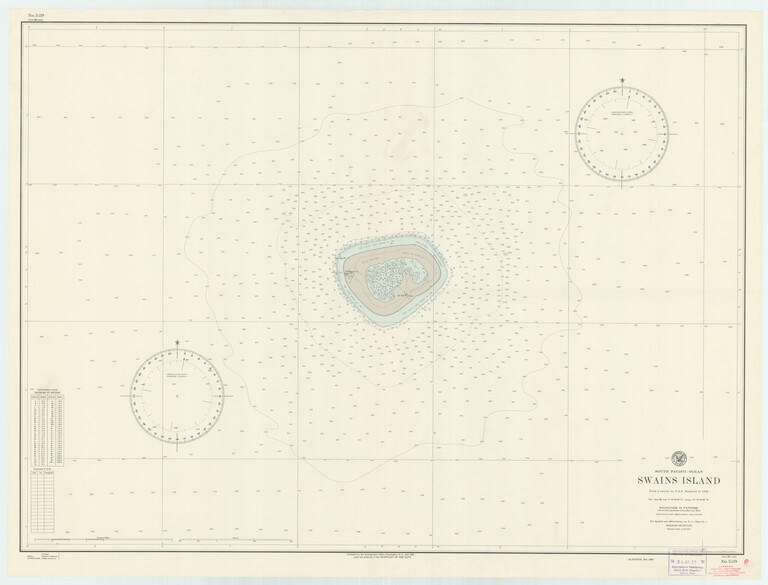

This map of the island is from a US survey in 1939, and was published in 1947.

Source: Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego, La Jolla, 92093-0175 (https://lib.ucsd.edu/sca)

Since 1856 Swains Island has been said to be privately owned by the family of American Eli Hutchinson Jennings Snr. Reportedly, Jennings purchased the “title” to the island for 15 shillings per acre and a bottle of gin from an Englishman Captain Alexander Turnbull, who also claimed to have discovered the island. For obvious reasons, there are ongoing questions about the legitimacy of that "purchase".

Embedded content: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ytII5iCoAnYIt was further complicated by an apparently fraudulent claim made by American Captain William W. Taylor, a whaler from Massachusetts, using the U.S. Guano Islands Act of 1856.

Essentially the Act gave Americans permission to plant a US flag on an uninhabited island or rock to mine the sought-after guano but that once the guano had been extracted, the US was not obliged to keep possession of the island or rock.

Captain Taylor duly claimed 43 islands in 1859 including Atafu, Fakaofo, Nukunonu and Olohega.

But as American writer Laray Polk penned in her 2021 exposé, it appears that Captain Taylor probably never set foot on any of the islands, and simply used an old chart to lodge his claim. In fact, 23 of islands didn’t actually exist and 10 were known to be inhabited, disqualifying them under the Act. But despite numerous deficiencies in his claim, the US State Department still certified the entirety of Taylor’s claim in 1860.

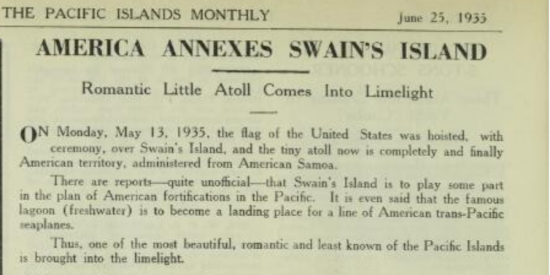

Source: Pacific Islands Monthly (1931) : PIM Retrieved October 25, 2022, from National Library of Australia.

The US eventually annexed Swains Island (Olohega) in 1925, giving the jurisdiction and administration of the island to American Samoa. Interestingly in this paper from the US State Department Archives, the US Secretary of State, Charles E. Hughes wrote to President Coolidge in 1924 virtually admitting that the US claim over Swains was unclear but given no-one else had a strong claim, they may as well annex it:

“The status of Swain’s Island so far as the jurisdiction of the United States is concerned cannot accurately be defined”

In 1980 the United States formally relinquished its “claim to sovereignty over the islands of Atafu, Nukunonu, Fakaofo” with the signing of the Treaty of Tokehega. In return, New Zealand agreed to abandon any claim to Olohega. While this trade-off is not explicitly stated, it is obliquely indicated in a clause pertaining to American Sāmoa, according to Polk.

In the lead up to the Treaty signing, New Zealand dissuaded the Tokelauans from pursuing Olohega, as its case was “weak and would not succeed in an international tribunal”.

Whether the Tokelauans who supported the treaty being signed fully appreciated the legal concepts or impact of the treaty based on the Tokelauan translation, is still being debated today. While officially the die has been cast, Tokelauans have continued to call for Olohega to be returned.

So, for the government of Tokelau to suggest, in May of 2022 that it will come up with a strategy for Olohega by 2025/26, is intriguing and potentially very bold. But one thing is certain, for Tokelau to plan for the future of Olohega, it will need to understand and properly address the past.

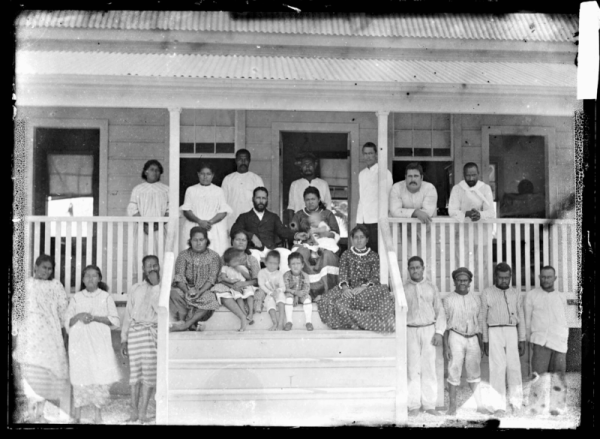

Source: Swains Island. From the album: Views in the Pacific Islands, 1886, Swains Island, by Thomas Andrew. Te Papa (O.037941)

The information on this site has been gathered from our content partners.

The names, terms, and labels that we present on the site may contain images or voices of deceased persons and may also reflect the bias, norms, and perspective of the period of time in which they were created. We accept that these may not be appropriate today.

If you have any concerns or questions about an item, please contact us.