Built digital for the Pacific

On October 6th, Leone Samu Tui from Auckland Museum and I presented at the 2021 MCN Virtual Conference.

The theme of this global event, which took place over October and November was 'What is Digital Now?"

Acknowledging the immense hardship and recalibration we’ve all had to endure over the past year, we invite you to consider “What is Digital Now?” This question encompasses the anxiety and uncertainty of the present while making space for curiosity and generative possibilities around how the future for digital technologies might look in museums.

This was my talk, the speaking notes transferred from the medium of a slide deck, presented live via a Zoom meeting into a blog post.

Kia ora koutou, I am here today to talk about the project I've had the privilege of leading, the Pacific Virtual Museum pilot, which is funded by the Department of Foreign Affairs & Trade in Australia, implemented by the National Library of New Zealand Te Puna Maatauranga o Aotearoa in collaboration with the National Library of Australia. The key aim of this project is to make visible and accessible the digitised cultural heritage of the Pacific. For people in and of the Pacific.

The key part of this pilot is the website: digitalpasifik.org

My talk today is some reflections on the considerations we made in regards to digital design, implementation and delivery of this site.

Built digital to be a bridge between worlds.

A key metaphor we’ve used for the design and purpose of this site is that its function is to serve as a bridge. A bridge between the worlds of museums, galleries, libraries - our content partners and the worlds of Pacific people.

The worlds of galleries, libraries, archives and museums (GLAM) sector, in particular those in the former and existing colonial powers hold tens of thousands of items, objects and records from the Pacific locations.

Most Pacific people are unaware that the GLAM sector holds these items and records.

As a bridge, we provide access, a starting point to enable Pacific people to access the source content and engage with the sites of our content partners.

As a bridge, we cannot be “sticky” in a digital way – we are happy for people to leave our site, if it means they are getting to our content partners.

This metaphor pushes at a default of website design, which is usually led by wanting users of your site to stay on your site. We want people to use our site to search and find content – but to engage with that content on your site.

Built digital for the realities of the Pacific:

We designed with digital constraints in mind.

We didn’t design with a New Zealand, Australian, US or European network defaults.

We designed for:

Low bandwidth/high cost mobile networks

We want the site to function well on 2G and 3G environments and also places where data is expensive. We aim to have no single page on the site be more than 800kb in size and that includes search result pages.

Mobile first

This means we don’t design for desktop browsers first. I’ve backlogged/stopped bug fixes on desktop browsers, in the interests of maximising developer time and spend.

We focus on design elements that function to make the key (not all) elements of metadata visible and accessible. This means we don’t embed anything. All audio/video is played on the content partners page.

Multiple languages across the Pacific means designing the interface to be icon first, simple and uncluttered, with a focus on less reading requirements.

As one of our user testers said - “I like it, because my Nana can speak English, but she can’t read it… she could figure this out”

Visual look and feel

We wanted the site to “reflect something of the Pacific back” to those using the site – to centre a Pacific narrative. Whilst it’s default function is to provide “search” - I asked our designer, "Let’s not make the home page a white one - like that search engine".

There are of course many languages across the Pacific, and we use English as a common language. We can edit the headers of most pages and can use local and indigenous languages as needed. To do so we use Contentful and can easily change header components as required.

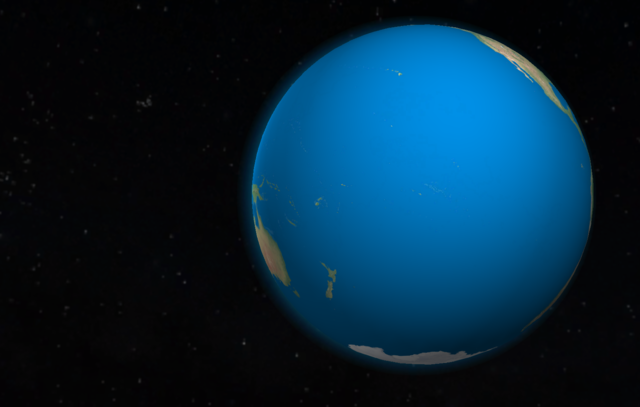

Lastly our home page design to make it easy to find stuff as a Pacific person. I reflected that our mental models of the blue continent is of ocean only - but if you’re from Chuuk, Marquesas, or Vanutu or Noumea - these islands, these coastlines are your home.

So the design and silhouettes of the locations, on the desktop derived homepage are designed to enable a person from this island to recognise (or discover) that shape, that place, that home - select it and see records in some way labelled with that location.

Digital using an agile methodology

I had some rough knowledge of the agile approach when I started, and fair to say, it’s still pretty rough - but we’ve been actively supported by our vendor Boost. And I know for some in the digital delivery space agile might be a default - but arguably it's not for the public service, and I also had the challenge of melding a Pacific way with a digital way.

We began this design and build in March of 2020, when Aotearoa was in lockdown. For us this has never been a tech project - it is a project about people. As such and in no small part because of the pandemic we had to work deliberately, particularly with Zoom only engagement, to make a space, to build relationships, provide understanding, be honest with what wasn’t clear.

It was my colleague Ulu, who quietly said in a retrospective - “I don’t know what these terms mean.” - which meant we specifically set aside time to check in every session, that people were aware of acronyms and terms - to enable them each to be part of the conversations that were needed to deliver this site.

The core foundations of the site, including Supplejack and the related cloud services were established in March/April of 2020 – and iterated on continually over the initial 20 weeks of build time.

We didn’t build an MVP to test ideas, and then start again. We started and have never stopped building. We’re not constantly building though - we pause to reflect budget constraints or user demands/requests.

We explored some ideas (natural language processing) that were not implemented – but work like this was timeboxed to prevent overspend.

We budget for ongoing monthly maintenance in between any funded development and feedback from co-design group and users. This co-design group met weekly to review/provide feedback/stop or approve the work that was being done by our designer and development team.

Built fully remotely using a co-design approach

Co-design as concept means many things to many people. My reflections here are on what we’ve set out to mean by co-design in a Pacific way.

The aim was to include voices of those in the Pacific, to understand how the pilot project could or should be of use to them. In January of 2020, we were hoping to travel to a number of these islands to build relationships and understand how to build a thing that fully supported them.

But global pandemic.

We engaged as much as possible with those across the ocean, using a range of online tools such as Zoom, Email, Slack. These tools were used asynchronously given the timezones involved. This included our design and development team – who we met only once face to face before our first lockdown in March of 2020.

We remain committed and open to onboarding individuals and orgs who hold and speak to Pacific cultural heritage. To have them be part of the conversation that informs this project. We set aside the budget and capacity to honour those contributions.

We have not been as successful as we could have been in this approach. Our site has been informed by a co-design group - but as a result of our online ony engagementthis has privileged those that are in locations with reliable network and in roles that enable them to join us.

Designed to make visible and accessible – but never take.

We are not a repository of digitized content.

Like Digital Public Libraries of America, Europeana and Trove, we leverage metadata from our content partners. We rely on the authority and due diligence of the content partner around metadata, and honour that.

We aim to work equitably on behalf of all content partners. We only share publicly accessible digitized records and share the respective copyright conditions applied by the content partner on each record. Our harvests of metadata are recurring, when metadata on a content partners site is updated or refreshed, we reflect those changes.

We are not into translation of metadata for the sake of an English audience - we only need to match fields in our schema, to ensure the front end functions - so we welcome metadata in any language.

If items or objects are held in the Pacific and the metadata is recorded in Chamorro or Tok Pisin, then we want to highlight that. Also the Traditional Knowledge label fields are built into our schema, so any content partner that is using them, we will display those. I’d like to acknowledge the work of Jane Anderson and Maui Hudson and their supportive conversations.

Importantly, we never take metadata - in the event of our site being shuttered – the content partners lose nothing, they are the holders of metadata. In terms of a Pacific wide experience of colonialism, and the legacy of taking of items – this was crucial for me. Digital colonisation and appropriation of culture is already taking place and we cannot be a space that enables that.

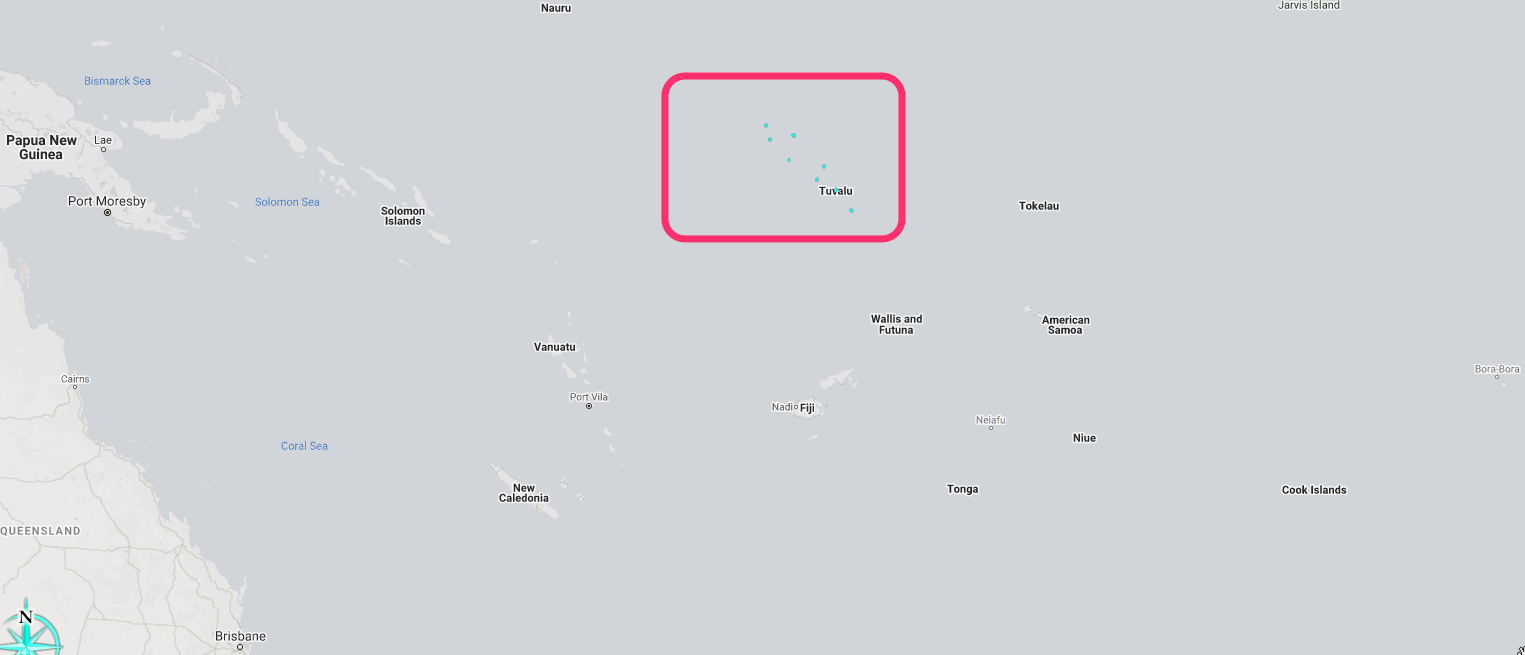

I’d like to finish with a story about one Pacific nation - Tuvalu.

You not be aware of Tuvalu the nation, but if you’ve used Twitch, and remember Fora or Ustream, you’ve used their domain name - that is of course, .tv

The land area of the 9 islands totals 26 square km, or 10.04 square miles. The average height above sea level for these islands is 1m.

Their economic zone covers an oceanic area of approximately 900,000 km² (347, 491 sq miles).

For reference the land area of Texas is 695,662 km². So technically one can say that Tuvalu is bigger than Texas.

They have a population of about 11,000 people.

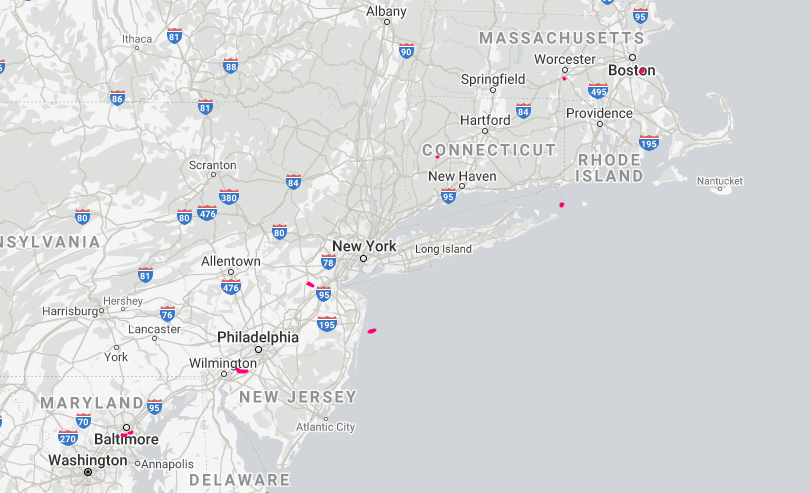

This is the nine islands of Tuvalu as pink dots against the Eastern seaboard of the USA.

As you consider this perspective, the scale and the multitudes of challenges for those living here, consider that it is currently served by satellite access for digital connectivity.

Current network speeds are about 1.5Mb down and 500kb up. There are plans to bring submarine cable and fibre access to the country.

This is the Tuvalu National Library and Archive, and it holds records dating back to the 1800s from when the islands were a British colony. We’ve had the immense privilege of meeting with their director Noa Petueli Tapumanaia, and hosting him and his staff in a webinar to shine a light on their mahi.

All of these museums hold hundreds of records, objects and images of Tuvalu.

If our project is enabled to share the metadata of those cultural heritage institutions, we can make those records visible and accessible to the people of Tuvalu.

The Pacific Ocean covers 33% of the surface area of the planet, but because our mental models of user needs and designing digitally are by default land based experiences – the Pacific Island locations, their cultures and their people are mostly invisible to us.

Or they are seen as singular remote exotic, idyllic locations.

But they are neither invisible, nor should they be romanticised.

Each of these locations and the people that are from these cultures are unique, vibrant, living and enduring. In the face of overwhelming challenges.

As my colleague Dr Tarisi Vunidilo said to me, pre-contact with the West, “we were astronomers, food scientists, mathematicians, sailors, artists and navigators - in our own right.”

And we forget that.

Opeta Alefaio said to us early on in our project, “It’s one thing for Pacific people to know they had their culture taken from them, it’s another thing entirely to not know the artefacts and records of that culture still exist”

Our hope is that our design, our leveraging of digital and our open engagement across this blue continent will enable Pacific people to know their culture, will recentre Pacific narratives and support generations of families and communities to connect with that culture that exists far from their islands.

Vinaka vaka levu sara.

Hero image by Cristian Palmer on Unsplash

The information on this site has been gathered from our content partners.

The names, terms, and labels that we present on the site may contain images or voices of deceased persons and may also reflect the bias, norms, and perspective of the period of time in which they were created. We accept that these may not be appropriate today.

If you have any concerns or questions about an item, please contact us.